Steve Jobs

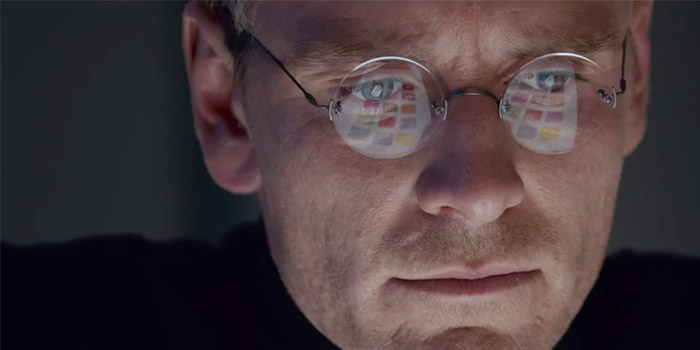

Life’s a beachball. Screenwriters can be typecast, just like actors. With Steve Jobs, Aaron Sorkin cements his reputation as the go-to guy for stories about brilliant young men with personality issues – flawed, obnoxious but dazzling wunderkinds who could, might, or in Jobs’s case actually did change the world somewhat, or at least got to ride the wave of change to shore as the competition wiped out. Emotionally bunkered, these youthful ubermensch finally grow when they find a reason to care about someone other than their fabulous selves. So it’s likely that on the strength of A Few Good Men Sorkin was sought out to portray facebook-founder Zuckerberg in The Social Network as an ethically dubious idea thief who nevertheless proves himself a worthy winner purely by virtue of being the smartest, sneakiest kid in the room. It’s almost certain Sorkin was consequently sought out to canonise Jobs as the obsessive, irresistable, empire-building narcissist we had to have. This is not to say either portrait is necessarily accurate or fair to the subject, nor that they are on the other hand without value. According to this telling, minutes before every product launch Jobs would be assaulted by living ghosts from his past, not unlike Scrooge, and roll around on the floor with them in paroxysms of autobiographical angst. And yes, Jobs finds his humanity when he discovers he is not after all above it. Though Michael Fassbender initially appears miscast as the young Jobs, this grows into one of his better performances.

|